Questioning my life choices

How did I find myself waking up in a cave in Montana? Or frantically seeking shelter from an electrical storm with an English man and a Belgian woman in the middle of Wyoming’s Great Basin? Or standing in a puddle recording the audio of nearby frogs while soaking wet and freezing cold in New Mexico? The answer to these questions begins 16 days and 2500 miles north of the frogs with 182 other bikepackers outside the Banff, Canada YWCA on June 10th ready to race the 2022 Tour Divide.

Into the cold unknown

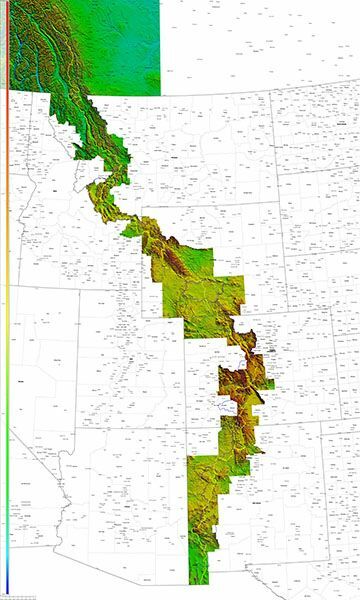

The Tour Divide is a bikepacking race that has grown from a single rider riding the Adventure Cycling Association’s Great Divide Mountain Bike Route through the Canadian and US Rocky Mountains as quickly as possible in 2005 to an annual Grand Depart loosely organized via Facebook and email with nearly 200 people this year (183 south-bounders and about a dozen north-bounders). The basic idea is to make your way to the start line in Banff, Canada by the second Friday in June and then pedal 2,715 miles south to the finish at the Mexican border in Antelope Wells, New Mexico – all while following the course under the watchful eye of satellite tracking devices, through rugged, unnamed dirt roads, trails, powerline accesses, and the occasional paved road, while also sticking to the self-supported ethos and rules established in 2005.

I made my way to the start via a long family drive from Alabama. My daughter wanted to visit Canada before starting college, and my wife and son are always up for an adventure, too. We explored the Badlands, Mount Rushmore, and Yellowstone before crossing over into Canada and exploring Calgary before heading to Banff. My radar camera captured a surreal moment a few days later rolling away from my son (blue sweatshirt), daughter (hoodie), and wife (taking cellphone video) knowing I wouldn’t see them again until finishing the race and riding home 4,500 miles. I didn’t need the radar camera for the Tour Divide itself, but rather for the 1,800 mile commute back home through New Mexico, Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi with lots of traffic.

Winter Storm Warning

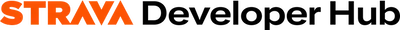

Canada offered breathtaking views of sharp, snow-covered mountains, which quickly morphed into the staggering reality of the challenge ahead when the course crossed the first of several high mountain passes, most of which were still covered by many feet of snow. For me, this made for an extra challenge because I have a permanent injury from being hit by a car while riding that makes it impossible for me to wear bike shoes for long rides. This meant I had to hike-a-bike through many miles of snow wearing sandals!

This year's weather was particularly nasty. Mild rain on Day 1 turned into cold rain on Day 2, which eventually turned into a late season winter storm on Day 3 dumping over a foot of fresh snow leading to helicopter rescues for thirteen racers. Once the race started, it was hard to keep track of the weather. Thankfully, my Garmin popped up weather alerts whenever I was in coverage. My feeling of surprise when seeing "Winter Storm Watch" turned to concern when the next message a few hours later was "Winter Storm Warning". This motivated me to pick up the pace as word on the Tour Divide grapevine was that the storm would have less of an impact the farther south and east you made it. I was fortunate to be just barely ahead of the worst of it.

Out of the snow and into the wind

After finally crossing through all the snow on Richmond Peak and dropping off the mountain, I stopped on a small rise standing in the sun so freezing cold and wet from the long descent that I simply could not go any farther while the sun was out and there was a bit of warmth. When the wind started to pick up again, I knew I had to keep going.

Shortly after starting again, another racer caught up as I stopped at a tree crossing. He remarked at how stupid the conditions were and that he was going to scratch in Seeley Lake. I mentioned that I was also going to head off course to Seeley Lake, buy a better rain jacket, and look for a place to do laundry. I encouraged him to reassess there before deciding to scratch. I never saw him again.

Seeley Lake, Montana had everything I needed. Saloon, laundry room with attached shower, coffee shop, and most importantly - clothes! The owner of the sporting goods store demonstrated his waterproof hunting jackets by blasting one with a hose. I bought one immediately, plus warm fingerless gloves with pullover mittens. Fully rejuvenated, fully showered, laundered, and coffeed up, I flew up the mountain back onto the course, almost literally, because of how strong the tailwind was and how much surface area my new jacket had.

Falling trees

The wind did not let up. Another Winter Storm Warning message reminded me that there was still a storm bearing down on me. The huge outflow associated with the storm pushed me with 25mph+ tailwinds through Ovando all the way to Lincoln. The cold rain started just as I made it to Lincoln, so I decided to resupply and take a break at the historic Lincoln Hotel.

By the time I left Lincoln, it had mostly stopped raining where I was - but behind me over a foot of snow had fallen up high in the mountain passes. Where I was, the wind continued unabated - particularly through a long technical singletrack section on top of Lava Mountain, where the wind was so strong that the sound of snapping limbs and falling trees was alarmingly frequent. I thought for sure one would fall on me. The wind, which had been mostly a tailwind, turned into a ridiculous headwind down one long descent. At one point, I was going downhill working hard against the wind when it shifted enough to turn me sideways and knock me off my bike. I had to wait until the gusts stopped to even remount and get started again. Thankfully, this nasty headwind only lasted for the "descent".

From freezing in a cave to hot headwind hell

After three mountain passes in all that wind, transitioning from deserted dirt roads to busy highway traffic in Helena, and finally navigating a steep tricky single track descent at night down into the largest city of the entire race (Butte, MT) for a short expensive hotel stop, I set out on a 200+ mile ride intending to make it from Butte all the way to Lima near the Idaho border. Along the way, I climbed and then walked/slid down from Fleecer Ridge with its notorious 25-35% double track descent before making it to the Wise River Mercantile and signing the guestbook. It's interesting to see your position in the race via the signatures of the racers ahead of you. You know the scope of a race is huge when time splits are measured in days and recorded in a guestbook rather than minutes and shown from a Tour de France motorcycle clipboard. Many hours later, I resupplied at the Horse Prairie Saloon before the 75 mile stretch to Lima on the infamous Bannack Road, known for many miles of mud when wet and a 25 mile long 3,000 foot climb.

The dirt road was hard as cement, so I started out before sunset riding fast, but it was midnight by the time I reached the top of the pass. The temperature had fallen down into the 30s again which forcing me to keep riding until I could find shelter, which turned out to be a cave a few miles into the long descent, which crawled up into and fell asleep in seconds.

I was surprised to wake up after sunrise and resumed my ride towards Lima and found myself parking my bike outside the cafe with four other TD racers and riders all arriving at the cafe at the same time. From frost to mid-morning heat, I discovered that my waterproof hunting jacket took up my entire backpack. Unable to even fully zip the backpack closed, the other racers laughed with me as I demonstrated how much room that jacket took up in the bag.

Climbing up into Idaho and West Yellowstone was a 50 mile long rough, washboarded gravel road with no shade and a stiff headwind. It was a tough mental battle through hot, headwind hell. By the end of this valley, I knew I could not carry that jacket all the way to Mexico, so I gave it away to a family at a visitor center I stopped at for water. Giving away a nice jacket knowing I would likely have to buy another was so bothersome to me that doubts started to creep in about whether I could finish the race. I started to consider turning east and riding straight home to Alabama. I quickly dismissed those thoughts knowing that line of thinking would be the end of my TD attempt.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times

I felt better after a short sleep in Island Park, Idaho leaving early before a beautiful, cold, wet sunrise riding through flooded trails and fields. I crossed over into Wyoming via the unpaved back entrance to Yellowstone and Grand Tetons National Parks. It was remote, scenic, and beautiful, but there were also a good number of dead trees fallen across the road from last summer's major forest fire that required dismounting, picking up the heavy bike up and over the tree, and then remounting again ... many times.

Still, the views of the Grand Tetons made it all worth it. The storm clouds started to move in as I worked my way up the long climb to Togwotee Pass. It started to rain and the dirt road quickly turned to mud. Little did I know how much this foreshadowed the night that lay ahead of me. After a brief stop at Togwotee Lodge while the thunderstorms passed, I set out around midnight under clear, cold skies.

Across the top of the pass, the Tour Divide route detoured off the paved highway onto a dirt road with a huge warning sign saying "DO NOT TRAVEL WHEN WET". The thunderstorms that had just come through a few hours earlier had left everything a muddy, snowy mess. It was the worst mud so far, mixed with unrideable snow hike-a-bike sections, too. Four hours later, I had made it down the eight mile descent freezing, soaking wet, and sleepy to a closed restaurant. I bundled up as much as I could and huddled right in front waiting for it to open.

Shortly before it opened, I was surprised to see three bikepackers emerge with their bikes from the lodge attached to the restaurant. They introduced themselves and said they were from Queenstown, New Zealand. Breakfast with them was a much needed break both mentally and physically. Afterward, I pulled away on the long, steep, muddy, and snowy climb up Union Pass topping out on a wind-swept 10,000' plateau with an ominous 360° view of 13,000' peaks in all directions.

An international crossing of the Great Divide Basin

After leaving the New Zealanders, I crashed into an ATV mud hole impaling my leg on a sharp stick drawing blood and raising concern of infection. ATV trails gave way to gravel roads, pavement, and tailwinds all the way to Pinedale. Frustrated with how often I was stopping, I decided to push on to the next town only to find the lodge had no vacancy. I begged for a closet to sleep in, but ended up having to backtrack to Pinedale adding 22 bonus miles to my TD adventure.

This turned out well because I didn't have to cross the 100 mile barren, muddy, and windy TD Great Basin alone. Three others had arrived in Pinedale: a Canadian (Theo), an Englishman (Steve), and a Belgian (Zoé) who was currently leading the women's race. I ran into Zoé as I was going the wrong way, and it was starting to rain. We both stopped and laughed at the absurdity of it all.

Steve caught me the next morning on the bike path with ominous clouds turning into several bouts of heavy, cold rain. The wind was at our backs so strong, though, that it felt at times like riding a motorcycle being pushed by the wind. We caught up to Zoé at the saloon in Atlantic City - the last populated place before the 100 mile crossing of the Great Basin. Zoé left first, followed a few minutes later by Steve and I, but a huge gust blew my gloves way down the road. By the time I retrieved them, Zoé was long out of sight and Steve was quickly disappearing, too. I started to panic a bit realizing how isolated it was out there. So I hit it hard and caught up to Steve several miles later as it became obvious that a very large storm was heading our way. Fearful of mud, we picked up the pace and were amazed that we were not making up any ground on Zoé.

As the storm was about to hit, we finally saw Zoé running towards us from a huge storage shed that had appeared from behind a hill. She also had been riding very, very hard to try to out-run the storm. In the supposedly completely barren basin, she had found a very large shed to house oil well machinery and equipment. And to our surprise and relief, it was unlocked! So we waited out the storm inside as lightning hit all around. The storm was over quickly, but one step outside and our feet were covered in thick mud. So we decided to rest a bit waiting for the mud to dry out.

The mud may have dried some by 2am when we left, but it was still nasty and sloppy for many miles all the way until sunrise where we noticed frost forming on what little vegetation was surviving alongside the gravel road we had made it onto leaving the mud behind.

The highs and lows all the way to Mexico

Crossing into Colorado and climbing up to Brush Mountain Lodge, the highlight stop of the entire route for everyone, was the best way to end the day. Riding through Colorado over the next few days was easily the best part of the entire route. I was too tired and sore to push the pace hard enough to struggle with the 12,000' elevation. Instead, I just climbed slowly and soaked in endless views of mountains and herds of elk.

Crossing into New Mexico started out great on a fast descent. But when I made it to Chama to resupply, I found out the town had been without drinking water for two weeks! I was able to load up with gas station supplies and set out on an authorized 100 mile paved detour that was still significantly faster than taking the more direct route that was impassable because of mud.

My time on the pavement ended almost exactly with the return of monsoons leading to the hardest ride I have ever done on a bicycle - crossing the Gila National Forest through storm after storm overnight with non-stop rain eventually taking me to that puddle of frogs I started this article with. I was so excited to hear the frogs because it meant there would be enough water for me to clean mud off the tires and drivetrain that had forced me to walk for many miles.

Even after making it out of the mud to Silver City, I still had to cross one more long section of New Mexico desert. The pioneer of the Tour Divide route, Matthew Lee, texted me about a re-route due to some flash flooding outside Silver City. In his last text, he noted that I should really enjoy the last day, specifically the Separ Desert, and how surreal it would be. He was right. The sweeping views of desert with not a single tree in sight anywhere were surreal - nothing like Alabama. I had several more encounters with mud on this final day. These were at low water crossings that had started to dry out so there wasn't much water, but all that was left behind was deep, sticky mud. Thankfully none of these lasted long, and at one that I guessed might be the last one, I followed the trickle of the water seeping out of the mud far enough downstream to find water deep enough that I could clean all the mud off my bike and my sandals. Through here in my efforts to avoid the mud, I ran over the first of four cactus thorns that punctured my front tire. Thankfully after a small gush of sealant when pulling out the thorns, my tire resealed itself each time.

It was through this desert that I called up Jeffrey Sharp, who runs the Hatchita Bike Ranch (a hostel for Tour Divide riders, cross-country riders, and continental divide hikers) about 45 miles north of the finish. He coordinates nearly everyone's extraction from the Mexican border. I also face-timed my family to show them several large tarantulas crossing the dirt road. I rolled into Hatchita to find two computer monitors loaded with all the tracking information so people in this city with a population of 52 could track riders as they arrived. I met 5 people (1/10th of the town) at the gas station while coordinating with Jeffrey to pick me up at the finish line. It was awesome to see him a few hours later where he snapped this picture of me below.

Many people struggle with the end of the race because after enduring everything, you eventually settle into a rhythm that becomes the new normal. As you approach the end and make it to the end, the thought of returning to the old normal life and all of its problems and challenges (and joys, too) can be a bit overwhelming. For me, I still had to cross some of the hottest parts of the country in July to get back home to Alabama so I knew that there were still many adventures ahead. And even making it back home to Alabama, I'm thankful for a good job that affords me such flexibility to travel in the summer, for my family and friends who make everything in life an adventure, and for the ability and desire to live each day as its own adventure whether it's just riding to work and back or riding across the country. In the end, it's all the same.

As J.R.R. Tolkien puts it in the Lord of the Rings, "He [Bilbo Baggins] often used to say there was only one Road; that it was like a great river: its springs were at every doorstep and every path was its tributary. 'It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out of your door,' he used to say. 'You step into the Road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there is no telling where you might be swept off to.'"

Look out for Parts 2 and 3 of my Tour Divide story by subscribing to the Tour Divide label to be notified when it's published.

Maps and data

I have linked below to maps of the race plus my partially successful attempt to ride home to Alabama. The TD map shows the route in yellow along with the Continental Divide itself in blue as well as highlighting all the provinces and counties traversed.